Writing a "Hello World!" bootloader and kernel for i386 from scratch in both C and Rust

Have you ever been curious what the software at the very earliest phases in the lifecycle of a running computer looks like?

Specifically, what kinds of tasks a bootloader might need to do to get an operating system kernel up and running?

If so, this is the correct post for you.

In this post, we will write a bootloader for the i386 architecture from scratch, which loads and transfers control to a kernel that knows how to do only a single thing: write the word "Hello World!" to the screen.

Because it seems interesting, we will write the "kernel" source in both C and Rust. In liueu of having access to a real system running on i386, we emulate the processor operations using QEMU. Table of contents

The above files are really the meat and potatoes of the project. However, for the Rust toolchain, we will be needing some additional helper files, so the final collection of files will also include these:

The kind of environment we will be emulating the software on will include the BIOS (Basic Input/Ouput System) firmware that's responsible for booting the hardware. This will put a constraint on our bootloader: the initial read that BIOS will do for us will only read 512 bytes from secondary storage. Because of this, our bootloader architecture will follow the structure typical for similar environments: the bootloader will simply consist of two stages, where the first stage does the bare minimum to load the second stage into memory, and the second stage will then contain the meat of our bootloader.

Sounds like a plan! So let's get to work in writing the first stage of the bootloader.

The very first thing we can start with is to let the assembler know that we will begin operations in 16-bit addressing mode. This is because of a backwards compatibility property of the IA-32 architecture: all x86-32 processors power on in a special 16-bit mode called the real mode. In this mode, the default register size is 16 bits and the maximum amount of addressable memory is 1 MiB. One of the main tasks of the second stage is in fact to switch from this 16-bit mode to the final 32-bit mode.

It will also be useful to store a reference to the memory address where the second stage instructions will ultimately begin. By design, the first stage program will consist of exactly 512 bytes, so this gives us 0x7c00 + 512 = 0x7e00 as the second stage start address.

At this point, we don't really have guarantees whether BIOS left or did not leave the segment registers in a sensible state, so we need to flush their values ourselves to gain independence of whatever BIOS has done before and to have a basic guarantee that we know what we are working with.

For most of the segment registers, this means writing them to a 0. For the Code Segment (CS) register, we need to do something different, since the architecture does not allow direct moves to the CS register. Due to this constraint, we need to write a value to the CS indirectly using a special form of instruction that's called a far jump.

This is an instruction of the form jmp segment:offset and it has the effect of setting to the CS register the value we provide in the segment bits; this can be a 0 for us. For the offset, we can just use a local label to the instructions where the flush all the other segments.

As to the other registers, we can't write to them directly; we must move values to them through a register such as AX. A common method[0] to zero a register is to XOR its value with itself. Before initializing the segment values, we disable interrupts with cli ("clear interrupt flag") so that nothing strange happens while the segment registers are in a transitory state.

After being informed about this interrupt, the Disk Services then looks at the values of a selection of registers to learn what it was asked to do. The first thing in executing a read from secondary storage through BIOS DS is therefore to encode in these registers the kind of a read we want to execute. Setting 0x02 as the value of the register AH signals that we want to execute a read:

But since we're going for of a minimal implementation with the target platform being emulated by QEMU, this is one point where we can just say, "there's no need" and halt if we weren't successful. If the read, on the other hand, went fine, we should continue onwards. The interrupt 0x13 uses the Carry Flag to signal success or failure, so we should test this flag with the jc ("jump if carry") instruction.

If the read was successful, however, at this point we are ready to hand the reins over to the second stage. We know the starting address of the second stage instructions, so all that is left to do is to jump to that address

The only that is left to be done now is to fulfill our contract with the BIOS by making sure that the first-stage program is exactly 512 bytes long and that the last two bytes constitute the special boot signature that BIOS expects to be there.

Sans the boot signature, we need to fill up 510 bytes. We know how to write filler bytes (with the db directive), so we just need to calculate how many such bytes we need to add for the padding. To do that, can calculate the difference between the addresses of the last directives/instructions (sans the signature) and the first directives/instructions.

Previously we mentioned the Current Location Counter symbol $, which can tell us the address of the current directive of instruction. To obtain the address of the first directive or instruction, we can use the Section Start Address symbol $$ which stands for the address that began the current section. Since our first-stage bootloader is just a flat binary file, this tells us the starting address of the first-stage program. It isn't absolutely necessary to use $$ here since we already know the starting address, but it's a nice touch.

The main task of the second-stage bootloader is to load the kernel code to a specific memory location and hand control over to that location, so at this point we can also define the address where we seek for the kernel code to begin. At that point we have already entered the protected mode, so that will be a 32-bit address. In the IA32 architecture, the 1 MiB mark is a natural address for that purpose.

For historical reasons, the mechanism to control the gate was wired in the PS/2 keyboard controller, which we will have to interface with to open the gate. The I/O ports we use to communicate with the controller are 0x64, which is used to query the controller's status and to inform the controller of incoming data, and 0x60 which is for communicating the actual data back and forth.

The thing to start with is to poll the 0x64 port repeatedly until we get a signal confirming that the controller is ready to receive a new command. The status of the controller is encoded in a single byte. The x86 assembly instruction to read data from an I/O port is in. The register the data is read to changes based on the size of the data that we want to read. Since we are reading a single byte, we must use the AL register

We will therefore test the value of this bit. If the bit is 0, we proceed onwards, but otherwise we continue to query port 0x64 for status information and wait for it to change. For this we use the familiar loop pattern:

Next we want to inform the controller that we are wish to write data to the data port 0x60. We communicate this also through port 0x64. The command to signal this intention is encoded by the byte 0xD1. As with the in instruction, the register responsible for writing byte-sized data is again AL. We therefore write this command to the register and send it to the port

We are now ready to load our Global Descriptor Table (GDT) into the CPU state using the lgdt ("load global decriptor table") instruction. The GDT is a data structure used by x86 processors to encode the characteristics of the existing memory segments, such as size, accessibility, and so on.

For now, assume that we have in our possession a 6-byte value gdt_desc that encodes two properties about our GDT: the first 2 bytes specify the size in bytes of the GDT, and the last 4 bytes specify the 32-bit memory address where our GDT begins. We will define this a bit later, but for now, assume that we have access to such a variable. We can therefore load our GDT for the CPU:

We can't modify the contents of CRO directly, so we do it indirectly by loading the value of CRO to the EAX register (EAX is the required register for this in the x86 IAS), modify the value there, and then send the modified value to CR0.

Although the CPU is now in the protected mode, it is in a kind of a transitory state, where there are possibly still data in the context of the 16-bit real mode laying around. What we need to do next is to flush this information, so that we can start with a clean slate. As we did before in the first stage, we do this by commencing a far jump.

For now, assume that we have already defined our GDT and that we have a segment selector for the Code Segment Descriptor in the GDT saved in the constant jmp CODE_SEG. Assuming that these are available, we can write the far jump instruction.

To initialize the stack, we first need to define where we would like the top of the stack to be located. We'll use labels to mark the top and bottom of our stack, and reserve 4 KiB of space for the stack using the resb directive.

As with the stack, we mark the beginning and end of the kernel image bytes. To direct the assembler to include the kernel binary, we use the incbin directive which takes as its argument the name of the binary file, which will be "kernel.bin". To know how many bytes we need to copy, we also need to count the bytes in the kernel image.

Before we can do that, we will need to copy the kernel binary to its correct memory location. The x86 hardware engineers have made this really straightforward for us by implementing the rep movsb instruction sequence, which is kind of a "hardware-level memcpy".

The arguments required by memcpy in the C standard library are a destination address, a source address, and the number of bytes to copy. For rep movsb, the contract is essentially the same. rep movsb assumes that each those arguments can be found in specified registers. In this case, the contract is that ESI holds the source address, EDI holds the destination address, and ECX contains the count of bytes to copy.

Earlier we embedded the kernel binary to the second-stage binary, so we know where to start copying from; that's the source address. In the very first lines we also defined the final memory address of the kernel; that's the destination address. And while embedding the kernel image, we counted how many bytes it consists of. We therefore have all the quantities required to fulfill the contract for rep movsb, so let's do that.

Our table will consist of three descriptors: the Null Descriptor, the Code Segment Descriptor, and the Data Segment Descriptor. The Null Descriptor consists of 8 bits while the Code Segment Descriptor and the Data Segment Descriptor both consist of 64 bits (two 32-bit values).

For historical reasons, the format of the Segment Descriptors is a bit scattered, and therefore scrutinizing the GDT internal state is a bit dry, but definitely important and necessary, so there's no way to avoid it!

The Segment Limit is a 20-bit sequence that consists of bits 0-15 and 16-19. The Segment Limit determines the size of the segment. The Granularity Flag, encoded in bit 50, determines how the bits in the Segment Limit are interpreted. If the Granularity Flag is clear, the Segment Limit can range from 1 byte to 1 MByte, in byte increments, and if the flag is set, then the Segment Limit can range from 5 KBytes to 4 GBytes, in 4 KByte increments. We want the segments to be the maximum size possible (4 GB), so we should set the bits 0-15, 16-19, and 50. Our segments would then look like this:

CS: 1111 1111 1111 1111 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 1000 1111 0000 0000

DS: 1111 1111 1111 1111 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 1000 1111 0000 0000

Next we need to choose the Base Address, which is a 32-bit value joined together from bits 16-39 and 56-63. This value defines the location of byte 0 of the segment within the 4 GByte linear address space. For maximum performance, although it's not a strict requirement, the base address should be aligned to 16-byte boundaries. The natural and simple choice here is to choose 0 as the base address. This keeps our DS and CS above unchanged.

Next comes a byte whose bits encode several different settings. Bits 0-3 encode the segment type, the bit 4 encodes the descriptor type, bits 5-6 encode the descriptor privilege level, and the bit 7 encodes the segment-present flag.

To configure the segments to be present in memory, we set bit 7. To declare that the segments are either code or data segments, we also set bit 4. The lowest four bits determine the type. The type we want for the Data Segment is plain Read/Write, so we look at the Intel manual for the corresponding value, which is 0010. For the Code Segment, the type we want is plain Execute/Read, so we should have the low bits 1010. After adding this byte, the descriptors now look like:

CS: 1111 1111 1111 1111 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 1001 1010 0000 1000 1111 0000 0000

DS: 1111 1111 1111 1111 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 1001 0010 0000 1000 1111 0000 0000

There's one more byte to add which encodes part of the limit value (the first low-order nibble) and four settings values, one of which (the granularity, bit 7) we have already added. Bit 6 encodes the default operation size flag. Both of our segments are 32-bit segments so we should have this bit set; 16-bit segments would have this bit cleared. Bit 5 encodes the 64-bit code segment flag. Since our segments are 32-bit, we should have this bit cleared. Finally, bit 4 is ignored by the CPU, so we can just leave it be zero. This means that the final segment bits are:

CS: 1111 1111 1111 1111 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 1001 1010 0000 1100 1111 0000 0000

DS: 1111 1111 1111 1111 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 1001 0010 0000 1100 1111 0000 0000

The x86 architecture also asks us to begin the GDT with a "Null Descriptor" that is used to guard against accidental references to unused segment registers. The Null Descriptor should be 8 bytes all 0. Given these bits, we can now define our GDT:

The start.asm is straightforward: we do only two things there. The first is to set up a fresh stack for the kernel to use, and the second is to call the kernel entry point function, which we assume to have the external symbol kmain.

One thing to note about the Makefile is that currently boot.bin and loader.bin are not dependent on each other, although in reality they are. Remember how in boot.bin we read 5 sectors (around 2.5 KiB) into memory? Since we are embedding the kernel in the loader.asm, the side of the loader binary can increase drastically, at which point reading 5 sectors would be too few. This dependency would be best to be explicit in the Makefile (or elsewhere), but for a "Hello World!" -type of implementation, we don't need to worry about that.

In particular, in this kind of a situation we need to be careful about compiler optimizations interfering with our control of the VGA. Suppose for example that we wrote the byte 0x00 to a given location of the array, then byte 0x01 to the same location, followed again by the byte 0x02. The nature of the VGA is that all of these changes could be visually followed as subsequent changes on the monitor state. However, an optimizing compiler could look at this instruction sequence and say, "the sequence starts at 0x00 and ends at 0x00; let's keep only the last step". For these kinds of reasons, we want to instruct the compiler to not optimize memory accesses to this data structure. We can accomplish this with the volatile keyword.

Now our print function should just take the bytes of the string "Hello World!" and write each byte to the VGA, starting from the very first index.

The Rust kernel

Next we just need to write a corresponding Rust kernel that behaves in the same way.

In the Rust side, we need to do a little bit of configuration work to configure the compiler to compile for the i386 architecture.

Everything starts from the cargo.toml.

The Rust kernel

Next we just need to write a corresponding Rust kernel that behaves in the same way.

In the Rust side, we need to do a little bit of configuration work to configure the compiler to compile for the i386 architecture.

Everything starts from the cargo.toml.

Next up we need to tell the compiler that instead of compiling to the local architecture, we want to cross-compile to the i386 architecture. This we can do by configuring .cargo/config.toml: which is what was expected.

References

[0] George Pólya: "An idea which can be used once is a trick. If it can be used more than once, it becomes a method."

which is what was expected.

References

[0] George Pólya: "An idea which can be used once is a trick. If it can be used more than once, it becomes a method."

[1] Intel® 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer Manuals Glossary

Repository

https//github.com/kaspell/hello386

In this post, we will write a bootloader for the i386 architecture from scratch, which loads and transfers control to a kernel that knows how to do only a single thing: write the word "Hello World!" to the screen.

Because it seems interesting, we will write the "kernel" source in both C and Rust. In liueu of having access to a real system running on i386, we emulate the processor operations using QEMU. Table of contents

- Introduction

- Bootloader first stage

- Bootloader second stage

- Linker script and Makefile

- The kernels

- References

- Glossary

- Repository

- boot.asm

- kernel.c / kernel.rs

- linker.ld

- loader.asm

- Makefile

- start.asm

The above files are really the meat and potatoes of the project. However, for the Rust toolchain, we will be needing some additional helper files, so the final collection of files will also include these:

- .cargo/config.toml

- Cargo.toml

- i386-elf.json

- rust-toolchain.toml

The kind of environment we will be emulating the software on will include the BIOS (Basic Input/Ouput System) firmware that's responsible for booting the hardware. This will put a constraint on our bootloader: the initial read that BIOS will do for us will only read 512 bytes from secondary storage. Because of this, our bootloader architecture will follow the structure typical for similar environments: the bootloader will simply consist of two stages, where the first stage does the bare minimum to load the second stage into memory, and the second stage will then contain the meat of our bootloader.

Sounds like a plan! So let's get to work in writing the first stage of the bootloader.

The very first thing we can start with is to let the assembler know that we will begin operations in 16-bit addressing mode. This is because of a backwards compatibility property of the IA-32 architecture: all x86-32 processors power on in a special 16-bit mode called the real mode. In this mode, the default register size is 16 bits and the maximum amount of addressable memory is 1 MiB. One of the main tasks of the second stage is in fact to switch from this 16-bit mode to the final 32-bit mode.

boot.asm

Besides initially loading only a fixed number of bytes to memory, another convention in the BIOS is that the initial instructions are loaded specifically to the memory address 0x7c00.

To take this into account, the next thing we need to do is to direct the assembler to calculate all memory addresses of labels and data as if the instructions started at the address 0x7c00.

1; boot.asm

2bits 16

It will also be useful to store a reference to the memory address where the second stage instructions will ultimately begin. By design, the first stage program will consist of exactly 512 bytes, so this gives us 0x7c00 + 512 = 0x7e00 as the second stage start address.

boot.asm

At this point, we can start the first-stage bootloader code proper. The first thing we need to do is to initialize all the segment registers to sensible values to ensure

that they don't contain anything that might interfere with our later instructions.

A segment register is a 16-bit register inside the CPU that points to a block of memory (a segment).

Due to design choices in architectures preceding the i386, memory was segmented into segments, so in the i386 there are four segment registers: CS (Code Segment), DS (Data Segment), SS (Stack Segment), and ES (Extra Segment).

For the most part, we don't need to consider ourselves with the memory segmentation model; for our purposes for now, it's mostly useful to know that these registers exist and that they should at certain points be handled in a sensible way.

4FIRST_STAGE_START_ADDR equ 0x7c00

5SECOND_STAGE_START_ADDR equ 0x7e00

6

7org FIRST_STAGE_START_ADDR

At this point, we don't really have guarantees whether BIOS left or did not leave the segment registers in a sensible state, so we need to flush their values ourselves to gain independence of whatever BIOS has done before and to have a basic guarantee that we know what we are working with.

For most of the segment registers, this means writing them to a 0. For the Code Segment (CS) register, we need to do something different, since the architecture does not allow direct moves to the CS register. Due to this constraint, we need to write a value to the CS indirectly using a special form of instruction that's called a far jump.

This is an instruction of the form jmp segment:offset and it has the effect of setting to the CS register the value we provide in the segment bits; this can be a 0 for us. For the offset, we can just use a local label to the instructions where the flush all the other segments.

As to the other registers, we can't write to them directly; we must move values to them through a register such as AX. A common method[0] to zero a register is to XOR its value with itself. Before initializing the segment values, we disable interrupts with cli ("clear interrupt flag") so that nothing strange happens while the segment registers are in a transitory state.

boot.asm

At this point we should also initialize a value for the stack pointer.

We certainly want a value that won't interfere with the instructions we set forth here. Since the stack grows downward

from higher addresses, a safe value here is to the address where the first stage begins. We have already defined this value,

so we can use that here.

9start:

10cli

11jmp 0x0000:.init_segment_registers

12.init_segment_registers

13xor ax, ax

14mov ds, ax

15mov es, ax

16mov ss, ax

boot.asm

There are two steps left in our initialization process. When BIOS starts our bootloader it provides us the Boot Drive ID in the DL

register. This byte contains the information about the storage medium that BIOS found our bootloader program in. We are not too much

interested in this information for its own sake in this case, but when we later interface again with BIOS through its interrupts, the DL

register containing the Boot Drive ID is one argument to those interrupts, so we should be careful to preserve it. After we have stored the

ID in memory, we can also enable interrupts again with sti ("set interrupt flag").

18mov sp, FIRST_STAGE_START_ADDR

boot.asm

We'll declare this memory location near the end of our program so that there won't be any conflicts.

This first-stage bootloader is just a flat binary file, so if the CPU would encounter the memory directives here in the midst of the instructions,

it would interpret those as instructions and Very Bad Things could happen.

20mov [BOOT_DRIVE_ID], dl

21sti

boot.asm

Now we are ready for the main task in the first stage: to load the second-stage bootloader into memory and to hand control over to it.

We don't currently possess any ability ourselves to read bytes from any secondary storage, so we have to rely on BIOS to do this for us.

We ask BIOS to do this by firing a special 0x13 interrupt in the CPU that is the interrupt dedicated for yielding control to the

BIOS Disk Services.

40BOOT_DRIVE_ID db 0x00

After being informed about this interrupt, the Disk Services then looks at the values of a selection of registers to learn what it was asked to do. The first thing in executing a read from secondary storage through BIOS DS is therefore to encode in these registers the kind of a read we want to execute. Setting 0x02 as the value of the register AH signals that we want to execute a read:

boot.asm

To the register AL we write the number of sectors we want to read.

23mov ah, 0x02

boot.asm

Next comes some additional options for the read.

We want to start reading from sector 2, since the first sector contains our first-stage bootloader

Since the BIOS interface dates from a while back, we also give values to options such as Cylinder number and umber in registers CL and DH, respectively. These can just be 0s.

24mov al, 5

boot.asm

The address to load the data is also needed. In the beginning, we already defined the starting address of the second stage program.

25mov ch, 0

26mov cl, 2

27mov dh, 0

boot.asm

As mentioned before, the DL register with the Boot Drive ID is one argument to the interrupt, so at this point we make sure that the register contains the original value:

28mov bx, SECOND_STAGE_START_ADDR

boot.asm

Now the auxiliary data is in place, so we can fire the actual interrupt:

29mov dl [BOOT_DRIVE_ID]

boot.asm

At this point the read may or may not have been successful.

If the read wasn't successful, it would be best practice to try a few more times by using the loop pattern.

Especially on actual hardware it could be plausible that the finicky storage mediums might fail a couple times but then succeed afterwards, so

a couple failed reads shouldn't be a real reason to panic out of our bootloader.

30int 0x13

But since we're going for of a minimal implementation with the target platform being emulated by QEMU, this is one point where we can just say, "there's no need" and halt if we weren't successful. If the read, on the other hand, went fine, we should continue onwards. The interrupt 0x13 uses the Carry Flag to signal success or failure, so we should test this flag with the jc ("jump if carry") instruction.

boot.asm

The halt routine disables interrupts, instructs the processor to halt, and includes an additional jmp instruction to protect against any nonmaskable interrupts that might fire.

32jc halt

boot.asm

One could also accomplish a halt procedure by using the Current Location Counter $ in the following way:

36halt:

37cli

38hlt

39jmp halt

Don't do this!

However, this would essentially be busy-looping the CPU which would needlessly drain resources, which would not be good.

36halt:

37jmp $

If the read was successful, however, at this point we are ready to hand the reins over to the second stage. We know the starting address of the second stage instructions, so all that is left to do is to jump to that address

boot.asm

That then concludes the runtime CPU instructions for our first-stage bootloader!

34jmp SECOND_STAGE_START_ADDR

The only that is left to be done now is to fulfill our contract with the BIOS by making sure that the first-stage program is exactly 512 bytes long and that the last two bytes constitute the special boot signature that BIOS expects to be there.

Sans the boot signature, we need to fill up 510 bytes. We know how to write filler bytes (with the db directive), so we just need to calculate how many such bytes we need to add for the padding. To do that, can calculate the difference between the addresses of the last directives/instructions (sans the signature) and the first directives/instructions.

Previously we mentioned the Current Location Counter symbol $, which can tell us the address of the current directive of instruction. To obtain the address of the first directive or instruction, we can use the Section Start Address symbol $$ which stands for the address that began the current section. Since our first-stage bootloader is just a flat binary file, this tells us the starting address of the first-stage program. It isn't absolutely necessary to use $$ here since we already know the starting address, but it's a nice touch.

boot.asm

Finally, we declare the boot signature as the last two bytes:

42PADDING_BYTES_COUNT equ 510 - ($ - $$)

43times PADDING_BYTES_COUNT db 0

boot.asm

And that's it for the first-stage bootloader! The full file now appears as:

45db 0x55

46db 0xaa

boot.asm

Bootloader second stage

In the second stage it's our goal to start operating in the 32-bit mode, but we're not there yet.

Currently we're still operating in the 16-bit real mode, so we can helpfully inform the assembler about that fact.

1; boot.asm

2bits 16

3

4FIRST_STAGE_START_ADDR equ 0x7c00

5SECOND_STAGE_START_ADDR equ 0x7e00

6

7org FIRST_STAGE_START_ADDR

8

9start:

10cli

11jmp 0x0000:.init_segment_registers

12.init_segment_registers

13xor ax, ax

14mov ds, ax

15mov es, ax

16mov ss, ax

18mov sp, FIRST_STAGE_START_ADDR

19

20mov [BOOT_DRIVE_ID], dl

21sti

22

23mov ah, 0x02

24mov al, 5

25mov ch, 0

26mov cl, 2

27mov dh, 0

28mov bx, SECOND_STAGE_START_ADDR

29mov dl [BOOT_DRIVE_ID]

30int 0x13

31

32jc halt

33

34jmp SECOND_STAGE_START_ADDR

35

36halt:

37cli

38hlt

39jmp halt

40

41

42BOOT_DRIVE_ID db 0x00

43

44PADDING_BYTES_COUNT equ 510 - ($ - $$)

45times PADDING_BYTES_COUNT db 0

46

47db 0x55

48db 0xaa

loader.asm

The first stage instructions ended by jumping to execute instructions at the beginning of the second-stage program, which was the address 0x7e00.

For documentational purposes, we can define a constant with that address and then use the constant to inform the assembler that all addresses should be interpreted with reference to that starting point.

1; loader.asm

2bits 16

The main task of the second-stage bootloader is to load the kernel code to a specific memory location and hand control over to that location, so at this point we can also define the address where we seek for the kernel code to begin. At that point we have already entered the protected mode, so that will be a 32-bit address. In the IA32 architecture, the 1 MiB mark is a natural address for that purpose.

loader.asm

Entering into the 32-bit protected mode

We are still operating in real mode, so addresses for now should be treated in the 16-bit mode context. One of the main purposes of the second

stage is to enter the 32-bit protected mode, which we will do as the very first thing.

The first thing to do in preparing to enter the protected mode is to disable interrupts. Since this is a multi-instruction process, an interrupt

firing in the midst of it could bring the CPU to an unstable state. By disabling interrupts at this point, we seek to make this operation as atomic as possible.

4KERN_START_ADDR equ 0x00100000

5SECOND_STAGE_START_ADDR equ 0x7e00

6

7org SECOND_STAGE_START_ADDR

loader.asm

The next blocks of code are a bit unfortunate since they both form the majority of the lines we need to write to enter into the protected mode,

while also having as their only purpose providing backward compatibility to older CPUs. However, it is a necessity to include them.

10section .text

11start:

12cli

For historical reasons, the mechanism to control the gate was wired in the PS/2 keyboard controller, which we will have to interface with to open the gate. The I/O ports we use to communicate with the controller are 0x64, which is used to query the controller's status and to inform the controller of incoming data, and 0x60 which is for communicating the actual data back and forth.

The thing to start with is to poll the 0x64 port repeatedly until we get a signal confirming that the controller is ready to receive a new command. The status of the controller is encoded in a single byte. The x86 assembly instruction to read data from an I/O port is in. The register the data is read to changes based on the size of the data that we want to read. Since we are reading a single byte, we must use the AL register

loader.asm

After this instruction has executed, the bits of the byte in AL then encode information about the controller's current state. The bit we are interested

in is the second bit, which encodes the Input Buffer Full (IBF) flag. If this bit is set, the controller is busy processing some previous

command, but if the bit is cleared, it means that the controller's input buffer is empty, it is ready to receive a new command through the gate 0x60, and we can

proceed.

14in al, 0x64

We will therefore test the value of this bit. If the bit is 0, we proceed onwards, but otherwise we continue to query port 0x64 for status information and wait for it to change. For this we use the familiar loop pattern:

loader.asm

The "test" instruction executes an internal, nondestructive AND and updates the CPU's Zero Flag (ZF) based on the result. Since we

are ANDing the byte in AL with the byte 2 = 0000 0010, this has the effect of setting the Zero Flag to 0 should the Input Buffer Flag

in AL be 0 and to 1 otherwise. The conditional jump jnz ("jump not zero") instruction checks the value of the Zero Flag and sets the PC

to the memory address of the stated label if the Zero Flag is set, but otherwise does nothing. This is exactly what we want.

13wait:

14in al, 0x64

15test al, 2

16jnz. wait

Next we want to inform the controller that we are wish to write data to the data port 0x60. We communicate this also through port 0x64. The command to signal this intention is encoded by the byte 0xD1. As with the in instruction, the register responsible for writing byte-sized data is again AL. We therefore write this command to the register and send it to the port

loader.asm

At this point we need to wait again for the port to process our command and signal that it is ready to receive

the actual data. For this, we use exactly the same loop pattern as before:

17mov al, 0xd1

18out 0x64, al

loader.asm

After the first time the test fails, it means the controller has signaled that it is ready to receive the data.

At this point, we can commence the command that opens the A20 gate.

19wait2:

20in al, 0x64

21test al, 2

22jnz .wait2

loader.asm

That's it, the A20 gate is now open!

23mov al, 0xdf

24out 0x60, al

We are now ready to load our Global Descriptor Table (GDT) into the CPU state using the lgdt ("load global decriptor table") instruction. The GDT is a data structure used by x86 processors to encode the characteristics of the existing memory segments, such as size, accessibility, and so on.

For now, assume that we have in our possession a 6-byte value gdt_desc that encodes two properties about our GDT: the first 2 bytes specify the size in bytes of the GDT, and the last 4 bytes specify the 32-bit memory address where our GDT begins. We will define this a bit later, but for now, assume that we have access to such a variable. We can therefore load our GDT for the CPU:

loader.asm

At this point, we have everything ready to instruct the CPU to enter into the 32-bit protected mode.

The process of entering the protected mode happens by modifying the state of the CR0 register.

According to the IA-32 manual[1], the CR0 register "contains system control flags that control operating mode and states of the processor"

The Protection Enable flag is encoded by the bit 0 in CR0. When set, this flag enables the protected mode.

26lgdt [gdt_desc]

We can't modify the contents of CRO directly, so we do it indirectly by loading the value of CRO to the EAX register (EAX is the required register for this in the x86 IAS), modify the value there, and then send the modified value to CR0.

loader.asm

Once the instruction on line 30 has finished, we have officially entered the protected mode. Congratulations!

28mov eax, cr0

29or eax, 1

30mov cr0, eax

Although the CPU is now in the protected mode, it is in a kind of a transitory state, where there are possibly still data in the context of the 16-bit real mode laying around. What we need to do next is to flush this information, so that we can start with a clean slate. As we did before in the first stage, we do this by commencing a far jump.

For now, assume that we have already defined our GDT and that we have a segment selector for the Code Segment Descriptor in the GDT saved in the constant jmp CODE_SEG. Assuming that these are available, we can write the far jump instruction.

loader.asm

Transferring control to the kernel

Now that we are operating in the 32-bit context, we can inform the assembler about this fact.

32jmp CODE_SEG:protected_mode_start

loader.asm

Similarly to when we initialized the segment registers when we entered from BIOS control to the first-stage instructions,

here we again initialize the state of the segment registers to start our life in the 32-bit mode.

The CS register is already handled by the far jump.

What we now want to do with all of the other segment registers is to instantiate a Flat Memory Model. We want to tell to the CPU,

"we don't want to deal with all the different segments, we just want to control a flat 4 GiB address space". We do this by writing the same

data segment selector to all of the segment registers:

35bits 32

36

37protected_mode_start:

loader.asm

We also need to initialize the stack for the new context. In the first-stage bootloader, we dealt with the 16-bit sp

register, but in 32-bit mode our stack state is held in the extended stack pointer esp register.

The two are related: sp is just the 16 lowest-order bits of esp.

38mov ax, DATA_SEG

39mov ds, ax

40mov es, ax

41mov fs, ax

42mov gs, ax

43mov ss, ax

To initialize the stack, we first need to define where we would like the top of the stack to be located. We'll use labels to mark the top and bottom of our stack, and reserve 4 KiB of space for the stack using the resb directive.

loader.asm

Our final .bss section will contain just these stack parameters.

Having defined the stack addresses, we can initialize the 32-bit stack:

102section .bss

103stack_bottom:

104resb 4096

105stack_top:

loader.asm

At this point, let's also direct the assembler to include our kernel binary to the assembled second-stage binary.

This way, the second stage has access to the kernel code and then has the ability to move it to a suitable memory location.

45mov esp, stack_top

As with the stack, we mark the beginning and end of the kernel image bytes. To direct the assembler to include the kernel binary, we use the incbin directive which takes as its argument the name of the binary file, which will be "kernel.bin". To know how many bytes we need to copy, we also need to count the bytes in the kernel image.

loader.asm

Now we are nearing the molten core of our bootloader: transferring control over to the kernel.

95kern_img_start:

96incbin "kernel.bin

97kern_image_end:

98

99KERN_BYTES_COUNT equ kern_img_end - kern_img_start

Before we can do that, we will need to copy the kernel binary to its correct memory location. The x86 hardware engineers have made this really straightforward for us by implementing the rep movsb instruction sequence, which is kind of a "hardware-level memcpy".

The arguments required by memcpy in the C standard library are a destination address, a source address, and the number of bytes to copy. For rep movsb, the contract is essentially the same. rep movsb assumes that each those arguments can be found in specified registers. In this case, the contract is that ESI holds the source address, EDI holds the destination address, and ECX contains the count of bytes to copy.

Earlier we embedded the kernel binary to the second-stage binary, so we know where to start copying from; that's the source address. In the very first lines we also defined the final memory address of the kernel; that's the destination address. And while embedding the kernel image, we counted how many bytes it consists of. We therefore have all the quantities required to fulfill the contract for rep movsb, so let's do that.

loader.asm

When this instruction has completed, the kernel is in its final memory location, and there is only one final task:

to transfer control to the kernel. This requires just the familiar unconditional jump instruction.

47mov esi, kern_img_start

48mov edi, KERN_START_ADDR

49mov ecx, KERN_BYTES_COUNT

50rep movsb

loader.asm

Defining the Global Descriptor Table (GDT)

Now it has come the time to define the Global Descriptor Table (GDT) mentioned a few times earlier, a key data structure used by the CPU.

52jmp KERN_START_ADDR

Our table will consist of three descriptors: the Null Descriptor, the Code Segment Descriptor, and the Data Segment Descriptor. The Null Descriptor consists of 8 bits while the Code Segment Descriptor and the Data Segment Descriptor both consist of 64 bits (two 32-bit values).

For historical reasons, the format of the Segment Descriptors is a bit scattered, and therefore scrutinizing the GDT internal state is a bit dry, but definitely important and necessary, so there's no way to avoid it!

The Segment Limit is a 20-bit sequence that consists of bits 0-15 and 16-19. The Segment Limit determines the size of the segment. The Granularity Flag, encoded in bit 50, determines how the bits in the Segment Limit are interpreted. If the Granularity Flag is clear, the Segment Limit can range from 1 byte to 1 MByte, in byte increments, and if the flag is set, then the Segment Limit can range from 5 KBytes to 4 GBytes, in 4 KByte increments. We want the segments to be the maximum size possible (4 GB), so we should set the bits 0-15, 16-19, and 50. Our segments would then look like this:

CS: 1111 1111 1111 1111 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 1000 1111 0000 0000

DS: 1111 1111 1111 1111 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 1000 1111 0000 0000

Next we need to choose the Base Address, which is a 32-bit value joined together from bits 16-39 and 56-63. This value defines the location of byte 0 of the segment within the 4 GByte linear address space. For maximum performance, although it's not a strict requirement, the base address should be aligned to 16-byte boundaries. The natural and simple choice here is to choose 0 as the base address. This keeps our DS and CS above unchanged.

Next comes a byte whose bits encode several different settings. Bits 0-3 encode the segment type, the bit 4 encodes the descriptor type, bits 5-6 encode the descriptor privilege level, and the bit 7 encodes the segment-present flag.

To configure the segments to be present in memory, we set bit 7. To declare that the segments are either code or data segments, we also set bit 4. The lowest four bits determine the type. The type we want for the Data Segment is plain Read/Write, so we look at the Intel manual for the corresponding value, which is 0010. For the Code Segment, the type we want is plain Execute/Read, so we should have the low bits 1010. After adding this byte, the descriptors now look like:

CS: 1111 1111 1111 1111 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 1001 1010 0000 1000 1111 0000 0000

DS: 1111 1111 1111 1111 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 1001 0010 0000 1000 1111 0000 0000

There's one more byte to add which encodes part of the limit value (the first low-order nibble) and four settings values, one of which (the granularity, bit 7) we have already added. Bit 6 encodes the default operation size flag. Both of our segments are 32-bit segments so we should have this bit set; 16-bit segments would have this bit cleared. Bit 5 encodes the 64-bit code segment flag. Since our segments are 32-bit, we should have this bit cleared. Finally, bit 4 is ignored by the CPU, so we can just leave it be zero. This means that the final segment bits are:

CS: 1111 1111 1111 1111 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 1001 1010 0000 1100 1111 0000 0000

DS: 1111 1111 1111 1111 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 1001 0010 0000 1100 1111 0000 0000

The x86 architecture also asks us to begin the GDT with a "Null Descriptor" that is used to guard against accidental references to unused segment registers. The Null Descriptor should be 8 bytes all 0. Given these bits, we can now define our GDT:

loader.asm

At this point we can also define a value for the 6-byte variable gdt_desc from earlier. The first 2 bytes were supposed to

specify the size in bytes of our GDT, and the last 4 encode the 32-bit memory address where our GDT begins.

We can accomplish this as follows:

55section .data

56align 8

57

58gdt_start:

59db 0x00

60db 0x00

61db 0x00

62db 0x00

63db 0x00

64db 0x00

65db 0x00

66db 0x00

67gdt_code:

68db 0xff

69db 0xff

70db 0x00

71db 0x00

72db 0x00

73db 0x9a

74db 0xcf

75db 0x00

76gdt_data:

77db 0xff

78db 0xff

79db 0x00

80db 0x00

81db 0x00

82db 0x92

83db 0xcf

84db 0x00

loader.asm

Now we have a GDT defined, phew! For communication with other parts of the program, we still have to define a couple of selectors

87gdt_desc:

88dw gdt_end - gdt_null - 1

89dd gdt_null

loader.asm

This concludes the second-stage bootloader program.

91CODE_SEG equ gdt_code - gdt_null

92DATA_SEG equ gdt_data - gdt_null

loader.asm

Linker script and Makefile

At this point we should think a little bit about code organization, compiling, and linking.

Recall the seven "essential files" of the project from the intro:

1; loader.asm

2bits 16

3

4KERN_START_ADDR equ 0x00100000

5SECOND_STAGE_START_ADDR equ 0x7e00

6

7org SECOND_STAGE_START_ADDR

8

9

10section .text

11start:

12cli

13wait:

14in al, 0x64

15test al, 2

16jnz. wait

17mov al, 0xd1

18out 0x64, al

19wait2:

20in al, 0x64

21test al, 2

22jnz .wait2

23mov al, 0xdf

24out 0x60, al

25

26lgdt [gdt_desc]

27

28mov eax, cr0

29or eax, 1

30mov cr0, eax

31

32jmp CODE_SEG:protected_mode_start

33

34

35bits 32

36

37protected_mode_start:

38mov ax, DATA_SEG

39mov ds, ax

40mov es, ax

41mov fs, ax

42mov gs, ax

43mov ss, ax

44

45mov esp, stack_top

46

47mov esi, kern_img_start

48mov edi, KERN_START_ADDR

49mov ecx, KERN_BYTES_COUNT

50rep movsb

51

52jmp KERN_START_ADDR

53

54

55section .data

56align 8

57

58gdt_start:

59db 0x00

60db 0x00

61db 0x00

62db 0x00

63db 0x00

64db 0x00

65db 0x00

66db 0x00

67gdt_code:

68db 0xFF

69db 0xFF

70db 0x00

71db 0x00

72db 0x00

73db 0x9A

74db 0xCF

75db 0x00

76gdt_data:

77db 0xFF

78db 0xFF

79db 0x00

80db 0x00

81db 0x00

82db 0x92

83db 0xCF

84db 0x00

85gdt_end:

86

87gdt_desc:

88dw gdt_end - gdt_null - 1

89dd gdt_null

90

91CODE_SEG equ gdt_code - gdt_null

92DATA_SEG equ gdt_data - gdt_null

93

94

95kern_img_start:

96incbin "kernel.bin

97kern_image_end:

98

99KERN_BYTES_COUNT equ kern_img_end - kern_img_start

100

101

102section .bss

103stack_bottom:

104resb 4096

105stack_top:

- boot.asm

- kernel.c / kernel.rs

- linker.ld

- loader.asm

- Makefile

- start.asm

The start.asm is straightforward: we do only two things there. The first is to set up a fresh stack for the kernel to use, and the second is to call the kernel entry point function, which we assume to have the external symbol kmain.

start.asm

Here we defined the symbol _start and exported it so that our linker has visibility to it.

Now, in the linker file, we can declare _start as the entry point of our binary executable.

We will also guide the linker about the final ordering that we want the different sections to appear in, starting from the 1 MiB address.

1; start.asm

2bits 32

3

4extern kmain

5

6

7section .text

8global _start

9_start:

10mov esp, stack_top

11call kmain

12

13

14section .bss

15align 16

16

17resb 4096

18stack_top

linker.ld

Next, the Makefile. Since it's not of core interest here, let's just place it all in a single code block.

The Makefile implements the binary-building strategy mentioned earlier.

1/* linker.ld */

2ENTRY(_start)

3

4SECTIONS {

5. = 0x00100000;

6

7.text : {

8*(.text*)

9}

10

11.rodata : {

12*(.rodata)*

13}

14

15.data : {

16*(.data*)

17}

18

19.bss : {

20*(COMMON)

21*(.bss*)

22}

23}

One thing to note about the Makefile is that currently boot.bin and loader.bin are not dependent on each other, although in reality they are. Remember how in boot.bin we read 5 sectors (around 2.5 KiB) into memory? Since we are embedding the kernel in the loader.asm, the side of the loader binary can increase drastically, at which point reading 5 sectors would be too few. This dependency would be best to be explicit in the Makefile (or elsewhere), but for a "Hello World!" -type of implementation, we don't need to worry about that.

Makefile

This makefile implements the strategy of catenating the bootloader and the kernel into a single binary image.

Invoking with a plain make build, we build from the C source and with make build KERN_SRC=rust, we build using the Rust source.

The kernels

By this point, most of the work is done. What remains to be done is to write the kernel source files that each

1KERN_SRC ?= C

2

3OUT := os.img

4

5BOOT := ./boot.asm

6LOADER := ./loader.asm

7START := ./start.asm

8

9BOOT_BIN := $(BOOT:.asm=.bin)

10LOADER_BIN := $(LOADER:.asm=.bin)

11

12START_OBJ := $(START:.asm=.o)

13KERNEL_OBJ := kernel.o

14

15BOOTLOADER_SRC := $(BOOT) $(LOADER)

16BOOTLOADER_BIN := $(BOOT_BIN) $(LOADER_BIN)

17

18CRATE_NAME := rs_kern

19RUST_KERNEL_LIB := target/i386-elf/release/lib$(CRATE_NAME).a

20

21KERNEL_ELF := kernel.elf

22KERNEL_BIN := kernel.bin

23

24LINKER_SCRIPT := linker.ld

25

26OBJ := $(START_OBJ) $(KERNEL_OBJ)

27

28

29CC := x86_64-elf-gcc

30LD := x86_64-elf-ld

31AS := nasm

32OBJCOPY := x86_64-elf-objcopy

33QEMU := qemu-system-x86_64

34

35CFLAGS := -m32 -ffreestanding -nostdlib -Wall -Wextra -c

36LDFLAGS := -m elf_i386 -T linker.ld

37QFLAGS := -fda

38

39

40build: $(OUT)

41

42.PHONY: clean

43clean

44rm -f $(OBJ) $(BOOTLOADER_BIN) $(KERNEL_ELF) $(KERNEL_BIN) $(OUT)

45cargo clean

46

47run: $(OUT)

48$(QEMU) $(QFLAGS) $(OUT)

49

50$(OUT): $(BOOTLOADER_BIN) $(KERNEL_BIN)

51cat $(BOOTLOADER_BIN) $(KERNEL_BIN) >$(OUT)

52

53$(BOOTLOADER_BIN): $(BOOT) $(LOADER) $(KERNEL_BIN)

54$(AS) -f bin $(BOOT) -o $(BOOT_BIN)

55$(AS) -f bin $(LOADER) -o $(LOADER_BIN)

56

57%.bin: %.elf

58$(OBJCOPY) -O binary $< $@

59

60ifeq ($(KERN_SRC), rust)

61$(KERNEL_ELF): $(OBJ) $(LINKER_SCRIPT) $(RUST_KERNEL_LIB)

62$(LD) $(LDFLAGS) -o $(KERNEL_ELF) $(OBJ) $(RUST_KERNEL_LIB)

63else

64$(KERNEL_ELF): $(OBJ) $(LINKER_SCRIPT)

65$(LD) $(LDFLAGS) -o $(KERNEL_ELF) $(OBJ)

66endif

67

68$(RUST_KERNEL_LIB):

69cargo build --release

70

71%.o: %.c

72$(CC) $(CFLAGS) $< -o $@

73

74%.o: %.asm

75$(AS) -f elf32 $< -o $@

- Fulfills the contract required by start.asm and

- Prints the symbols "Hello World!"

- Halts

kernel.c

Here we assumed that we have defined a function kprint that accepts a pointer to a 0-termiinated string, which we will write soon.

Even though we are compiling C in a freestanding environment, we are still able to use some useful freestanding headers.

Let's start by including the stdint header that gives us some useful types.

17void

18kmain()

19{

20kprint("Hello world!");

21for (;;) { __asm__ __volatile__("hlt"); }

22}

kernel.c

We need to print characters to the screen and therefore we need to send inputs to the data structures that govern what exists on the screen.

In this case that data structure is the Video Graphics Array (VGA): a 4000-byte array from memory address 0xb8000 to 0xb8f9f, inclusive.

This is Memory Mapped I/O where data written to the array appears on the screen at the next refresh cycle.

This is critical information when it comes to modeling the structure in our kernel.

1#include <stdint.h>

In particular, in this kind of a situation we need to be careful about compiler optimizations interfering with our control of the VGA. Suppose for example that we wrote the byte 0x00 to a given location of the array, then byte 0x01 to the same location, followed again by the byte 0x02. The nature of the VGA is that all of these changes could be visually followed as subsequent changes on the monitor state. However, an optimizing compiler could look at this instruction sequence and say, "the sequence starts at 0x00 and ends at 0x00; let's keep only the last step". For these kinds of reasons, we want to instruct the compiler to not optimize memory accesses to this data structure. We can accomplish this with the volatile keyword.

4static volatile uint8_t *const VGA = (uint8_t *)0xb8000

kernel.c

For our purposes, we don't have a need to keep track of the end of the VGA since we are only writing a few symbols with no other actions.

And that's it! That concludes our C kernel.

7static void

8kprint(const char *s)

9{

10int idx = 0;

11for (; *s; ++s)

12VGA[idx++] = (uint8_t)*s;

13VGA[idx++] = 0x0f;

14}

15}

kernel.c

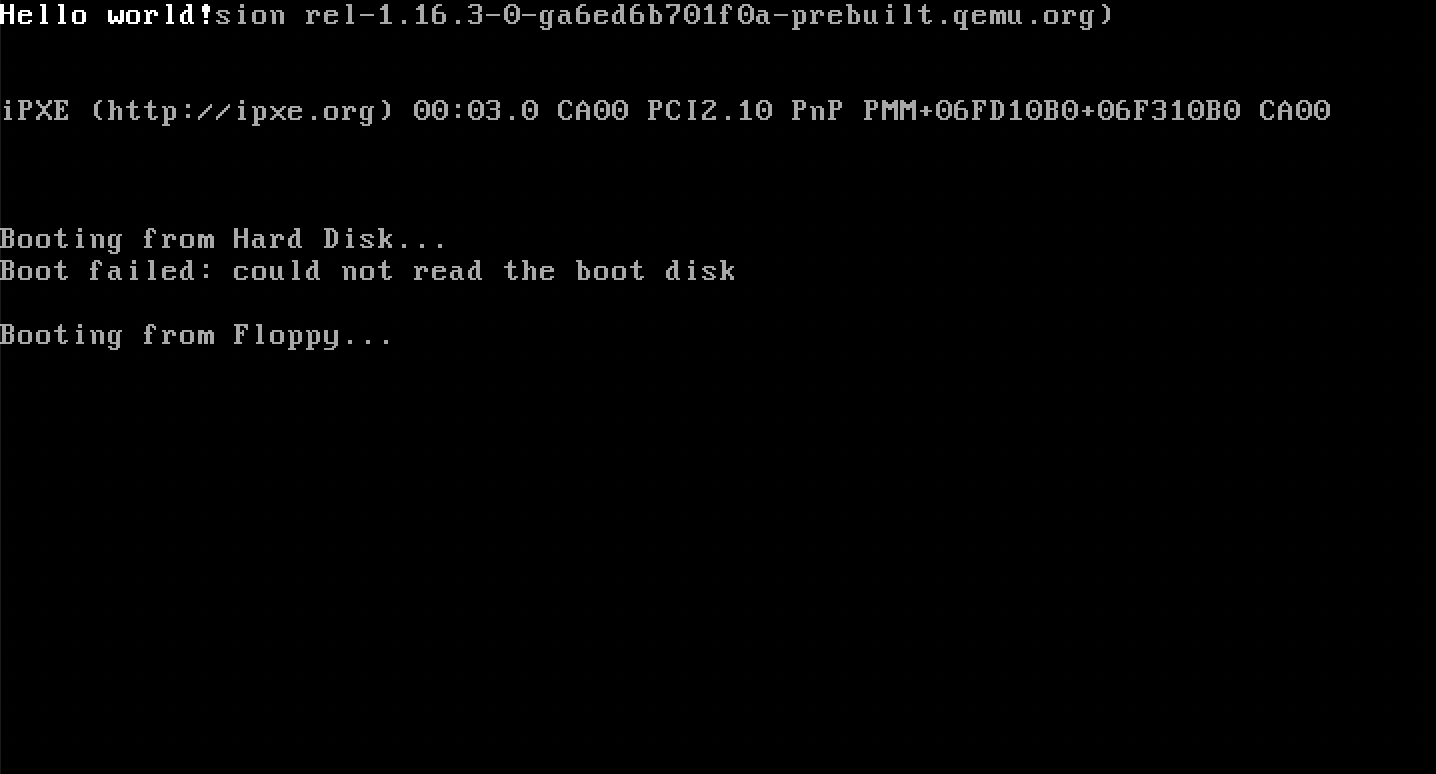

When invoking make run on a MacBook, one sees

1#include <stdint.h>

2

3

4static volatile uint8_t *const VGA = (uint8_t *)0xb8000

5

6

7static void

8kprint(const char *s)

9{

10int idx = 0;

11for (; *s; ++s)

12VGA[idx++] = (uint8_t)*s;

13VGA[idx++] = 0x0f;

14}

15}

16

17void

18kmain()

19{

20kprint("Hello world!");

21for (;;) { __asm__ __volatile__("hlt"); }

22}

The Rust kernel

Next we just need to write a corresponding Rust kernel that behaves in the same way.

In the Rust side, we need to do a little bit of configuration work to configure the compiler to compile for the i386 architecture.

Everything starts from the cargo.toml.

The Rust kernel

Next we just need to write a corresponding Rust kernel that behaves in the same way.

In the Rust side, we need to do a little bit of configuration work to configure the compiler to compile for the i386 architecture.

Everything starts from the cargo.toml.

cargo.toml

In cargo.toml, we tell cargo that we want to compile the kernel as a static library.

This allows us to let the start.asm be the "actual entrypoint" that just defers control to the kernel entrypoint.

Importantly, we also disable stack unwinding.

With stack unwinding turned on, after a panic, Rust would walk up the stack and invoke the destructors for the objects that had it.

But because we will be operating in a no_std environment, those runtime utilities would not exist.

Instead, we tell Rust, "when a panic occurs, call the panic handler that we will define for you".

1[package]

2name = "rs_kern"

3version = "0.1.0"

4edition = "2021"

5

6[profile.dev]

7panic = "abort"

8

9[profile.release]

10panic = "abort"

11

12[lib]

13name = "rs_kern"

14crate-type = ["staticlib"]

15path="kernel.rs"

Next up we need to tell the compiler that instead of compiling to the local architecture, we want to cross-compile to the i386 architecture. This we can do by configuring .cargo/config.toml:

.cargo/config.toml

Here, we instruct the compiler to cross-compile for the architecture that's described in the i386-elf.json file.the

We also instruct Cargo (by using an experimental, unstable feature, as of yet) to not use any pre-downloaded libraries and to the core library and compiler_builtins for the specific architecture we are targeting.

The i386-elf.json lists the properties of the target architecture:

1# .cargo/config.toml

2

3[build]

4target = "i386-elf.json"

5

6[unstable]

7build-std = ["core", "compiler_builtins"]

i386-elf.json

Because we configured Cargo in .cargo/config.toml to use an unstable, experimental feature, we need to rustup to use a Nightly version of the compiler that contains those unstable features.

1{

2"llvm-target": "i386-unknown-none",

3"data-layout": "e-m:e-p:32:32-p270:32:32-p271:32:32-p272:64:64-i128:128-f64:32:64-f80:32-n8:16:32-S128",

4"linker-flavor": "ld.lld",

5"target-pointer-width": "32",

6"target-c-int-width": 32,

7"arch": "x86",

8"os": "none",

9"cpu": "i386",

10"features": "-mmx,-sse",

11"disable-redzone": true,

12"executables": true

13}

rust-toolchain.toml

Now we can start writing the actual source code for the kernel.

We start by configuring that we want to compile in a no_std mode.

We also tell the compiler to not include the standard startup code since we are handling the entry by ourselves through start.asm.

1# rust-toolchain.toml

2

3[toolchain]

4channel = "nightly"

kernel.rs

On the C side, the freestanding -assumption was encoded in the compiling phase by giving gcc an appropriate flag.

On the Rust side, we encode this assumption directly in the source code file.

We also need to provide the panic handler function that we promised when configuring cargo.toml.

1#![no_std]

2#![no_main]

kernel.rs

The main function essentially is the same as in the C side.

The only additional things we need to include are some compatibility tools that ensure our compiled Rust binary is compatible with start.asm.

24#[panic_handler]

25fn panic(_info: &core::panic::PanicInfo) -> ! {

26loop {}

27}

kernel.rs

Here we given kmain the no_mangle attribute.

This ensures that the function name is not changed internally by the compiler; this is important because the contract with start.asm required that the kernel entry point function is called exactly kmain.

An additional thing we have done is we have specified an ABI specifier for the function, specifying to the compiler that we want this function compiled according to the C ABI.

This is the convention that start.asm expects and is therefore an implicit part of the contract.

Finally, we have specified in Rust syntax that the return value of the function is !, the Never Type.

This is just the syntax to declare that this function will never return to the caller.

Finally, we just add the VGA data structure and the kprint function:

18#[no_mangle]

19pub extern "C" fn kmain() -> ! {

20kprint("Hello World!");

21loop { unsafe { core::arch::asm!("hlt"); } }

22}

kernel.rs

The wraps up the Rust code! The whole file now looks like:

5static mut VGA: *mut u8 = 0xb8000 as *mut u8;

6

7

8fn kprint(s: &str) {

9for (idx, b) in s.bytes().enumerate() {

10let offset = 2 * idx;

11unsafe {

12core::ptr::write_volatile(VGA.add(offset), b);

13core::ptr::write_volatile(VGA.add(offset + 1), 0x0f);

14}

15}

16}

kernel.rs

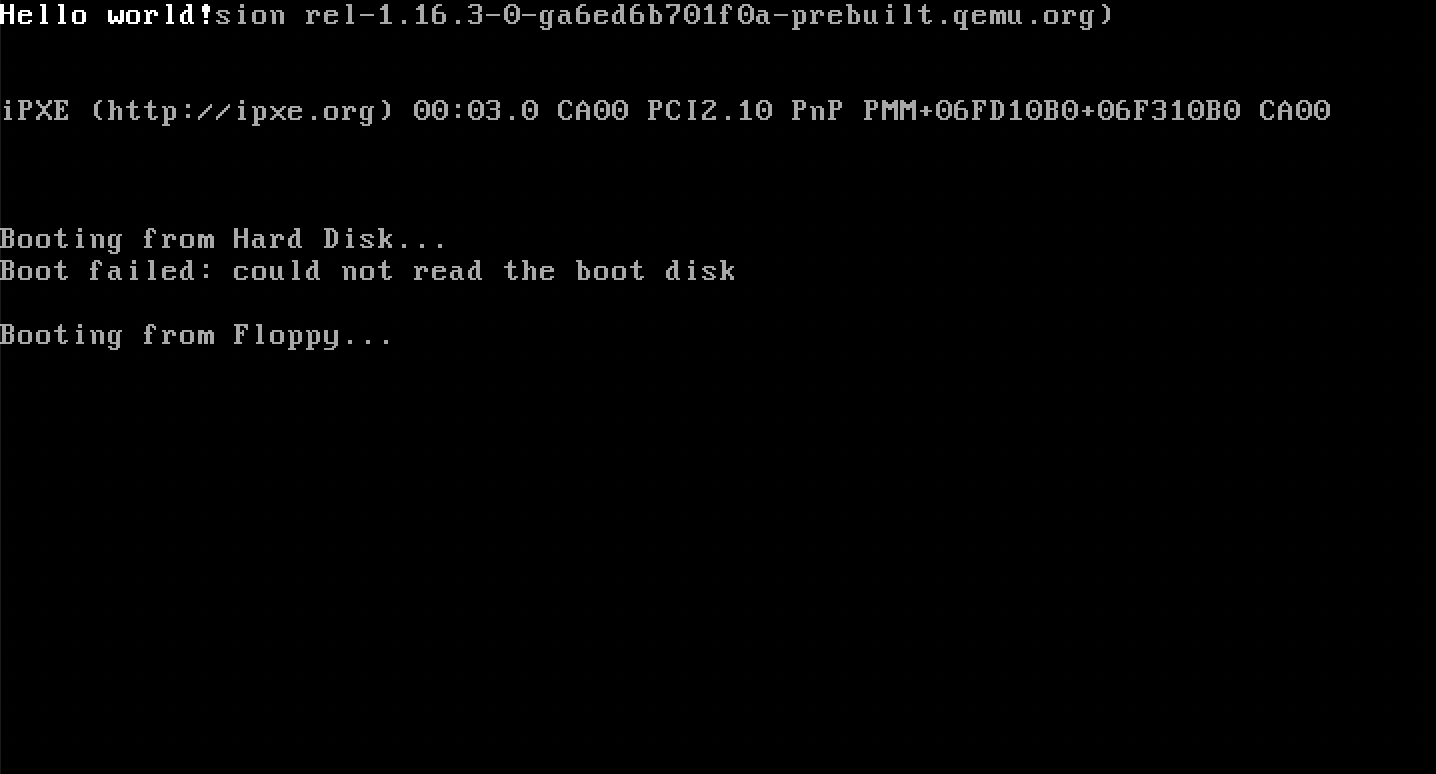

When running make run KERN_SRC=rust, we get

1#![no_std]

2#![no_main]

3

4

5static mut VGA: *mut u8 = 0xb8000 as *mut u8;

6

7

8fn kprint(s: &str) {

9for (idx, b) in s.bytes().enumerate() {

10let offset = 2 * idx;

11unsafe {

12core::ptr::write_volatile(VGA.add(offset), b);

13core::ptr::write_volatile(VGA.add(offset + 1), 0x0f);

14}

15}

16}

17

18#[no_mangle]

19pub extern "C" fn kmain() -> ! {

20kprint("Hello World!");

21loop { unsafe { core::arch::asm!("hlt"); } }

22}

23

24#[panic_handler]

25fn panic(_info: &core::panic::PanicInfo) -> ! {

26loop {}

27}

which is what was expected.

References

[0] George Pólya: "An idea which can be used once is a trick. If it can be used more than once, it becomes a method."

which is what was expected.

References

[0] George Pólya: "An idea which can be used once is a trick. If it can be used more than once, it becomes a method."[1] Intel® 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer Manuals Glossary

| A20 gate | A legacy electronic switch which, when enabled, allows the CPU to access memory addresses beyond the first 1 MiB. |

| BIOS (Basic Input/Output System) | Firmware that initializes hardware during the booting process while also providing certain runtime services (such as Disk Services). |

| BIOS Disk Services | A set of routines provided by the BIOS that allows programs to read from and write to secondary storage. |

| Bootloader | A program responsible for initializing the system hardware and loading the operating system kernel into memory from secondary storage. |

| Boot Drive ID | A unique identifier provided by the BIOS that tells the bootloader which storage device the system was booted from. |

| Extended Stack Pointer (ESP) | The 32-bit register responsible for pointing to the top of the stack in Protected Mode. |

| Far jump | A jump instruction in the IA32 architecture that changes the contents of both the instruction pointer and the Code Segment (CS) register. |

| Freestanding environment | A compilation environment where the standard library (in the C or Rust contexts) is not available. |

| Global Descriptor Table (GDT) | A data structure used by x86 processors in Protected Mode to encode the characteristics of any existing memory segments. |

| Inbut Buffer Full (IBF) flag | A status bit in the PS/2 controller indicating that the controller has received data but hasn't processed it yet. |

| Flat Memory Model | A memory management model in i386 where the operating system sees memory as a single, contiguous linear address space. |

| Never Type | A Rust type representing the return type of functions which never return to the caller. |

| Protected mode | A 32-bit operating mode of x86 CPUs that supports virtual memory, paging, and protection rings, and allows the system to address up to 4 GiB of memory. |

| Protection Enable flag | The specific bit in Control Register 0 (CR0) that switches the CPU from Real Mode to Protected Mode. |

| PS/2 keyboard controller | A legacy hardware chip the primary use of which was for input devices, but also had a special role in controlling the A20 gate. |

| Real mode | A 16-bit operating mode of x86 CPUs that the CPU initialize in for backwards compatibility. |

| Segment Limit | A 20-bit value inside a Segment Descriptor specifying the size of the segment. |

| Segment Selector | A 16-bit value loaded into a segment register in Protected Mode that acts as an index pointing to a specific Segment Descriptor in the GDT. |

| Video Graphics Array (VGA) | A display interface controller by a data structure of 2000 contiguous bytes starting at memory address 0xb8000. |